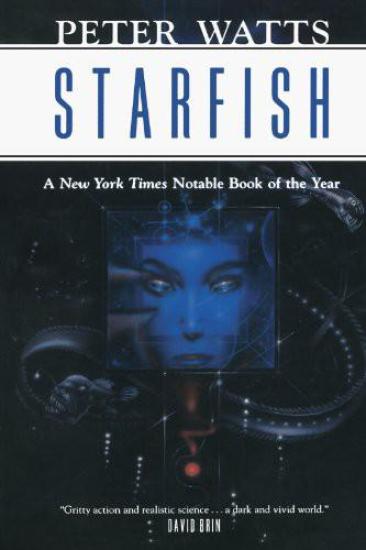

Series: Book 1 in the Rifters series

Rating: Not rated

Tags: EN-Alire, Lang:en

Summary

Civilization rests on the backs of its outcasts.

So when civilization needs someone to run generating

stations three kilometers below the surface of the

Pacific, it seeks out a special sort of person for its

Rifters program. It recruits those whose histories

have preadapted them to dangerous environments, people so

used to broken bodies and chronic stress that life on the

edge of an undersea volcano would actually be a step

up. Nobody worries too much about job satisfaction;

if you haven't spent a lifetime learning the futility of

fighting back, you wouldn't be a rifter in the first

place. It's a small price to keep the lights going,

back on shore.

But there are things among the cliffs and trenches of

the Juan de Fuca Ridge that no one expected to find, and

enough pressure can forge the most obedient career-victim

into something made of iron. At first, not even the

rifters know what they have in them—and by the time

anyone else finds out, the outcast and the

downtrodden have their hands on a kill switch for the

whole damn planet...

Peter Watts's first novel explores the last

mysterious place on earth--the floor of a deep sea rift.

Channer Vent is a zone of freezing darkness that belongs

to shellfish the size of boulders and crimson worms three

meters long. It's the temporary home of the maintenance

crew of a geothermal energy plant--a crew made up of the

damaged and dysfunctional flotsam of an overpopulated

near-future earth. The crew's reluctant leader, basket

case Lenie Clarke, can barely survive in the upper world,

but she quickly falls under the rift's spell, just as

Watts's magical descriptions of it enchant the reader:

"Steam never gets a chance to form at three hundred

atmospheres, but thermal distortion turns the water into

a column of writhing liquid prisms, hotter than molten

glass."

Watts is investigating monsters. Gigantic deep sea

monsters, surgically-altered-from-human monsters, faceless

jellied-brain computer monsters--which monsters are human,

which are more than human, which are less? Watts keeps the

story line stripped down to showcase the theme of

dehumanization. The anonymous millions who live along the

unstable shore of N'AmPac come under threat (a triggered

earthquake, and perhaps a disaster that's slower but even

more pitiless) from their own dehumanized creations. But

Watts is less interested in whether Lenie can save the dry

world as in whether she can save herself. In

Starfish, Watts stretches the boundaries of humanity up,

down, and sideways to see whether its dimensions reveal

anything we'd be proud to be a part of.

--Blaise Selby

Set in the early 21st century, Watts's debut

describes a future when the search for energy leads to

the tapping of geothermal sources deep in the ocean, as

in the Pacific's Juan de Fuca Rift, near Canada's

Northwest coast. The maintenance workers of the dangerous

underwater power plants are selected for their psychotic

tendencies, which enable them to forget their previous

lives on dry land, and are then surgically altered to

survive the intense pressure of the sea's abyssal depths.

These changes, which render the workers amphibious, also

leave them less than well equipped to face the threat of

powerful, archaic bacterialike creatures that proliferate

at the ocean bottom and use human hosts to carry them

upward to dry land, where their superior DNA could render

our species obsolete. The human resistance to these life

forms is described with a great deal of explicit violence

and graphic language, as well as well-orchestrated

paranoia that recalls the classic SF tale "Who Goes

There?" Watts's characterizations aren't strong but, as

in Arthur C. Clarke's The Deep Range, the underwater

setting and the technology employed there function as

characters in their own right, and quite vigorously. The

novel's pacing is excellent, making this, overall, a good

bet for beach reading. (July)

Amazon.com Review

From Publishers Weekly

Copyright 1999 Reed Business Information,

Inc.